Our History

Ancient roots

The Granta valley has been shaped by human settlement over thousands of years, with remains from the Mesolithic period onwards, with Roman villas and Angle and Saxon cemeteries nearby. The ancient Icknield Way passes close by; a network of tracks thought to date back c5,000 years to the Neolithic era, following the chalk from the Ridgeway in the West to Norfolk in the East. A Roman road forms the northern boundary of our parish, later known as the Wool Road to medieval traders and pilgrims. Nearby Hadstock was the site of a Christian monastery founded in the 7th century (before it was destroyed by marauding Danes 200 years later) and it is very likely that there has been a sacred place here by the crossing of the river since the early medieval period too. While the size and location of the Saxon church is unknown, we can say for certain that in the 11th and 12th centuries there was a Norman Church, built of clunch and rubble intermixed with Roman tiles. It had a long, narrow nave, a small chancel with a rounded end and a high pitched roof. Some parts of this Norman work survive in the present church: for example, there is an exterior arch near the south porch – seen as a half arch in the buttress by the tower.

The second pillar by the south aisle (at the west end) is also of Norman origin, as is the moulding on the inner part of the west doorway, and the three round clerestory windows.

The Changing Church

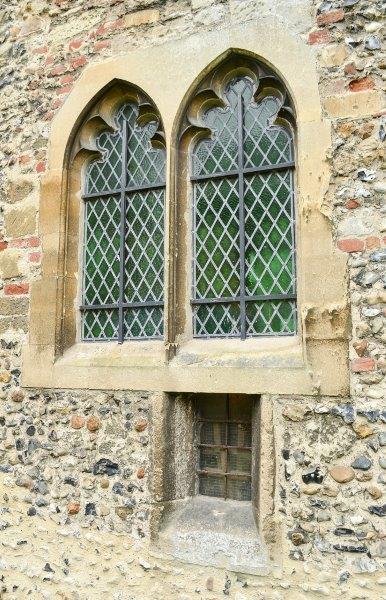

An almost new church was begun around 1308, built in the Early English and Decorated styles and made of flint, Roman tiles and ashlar. The nave was reduced in length, the south aisle was widened and the outer wall raised in height. The north wall of the old nave was demolished and a new north aisle was added to the Church. The chancel arch was enlarged, giving its present lop-sided appearance, and a decorated window was put in the northern outer wall overlooking the vestry.

In was in the 15th century, however, that our present Perpendicular Church was designed. All the perpendicular features evident today date from this period – including the large windows in the aisles and the nave (not the glass), and the two porches, with the remains of carvings like the beautiful heads of the king and queen on the south porch. The gargoyles were also added at this time.

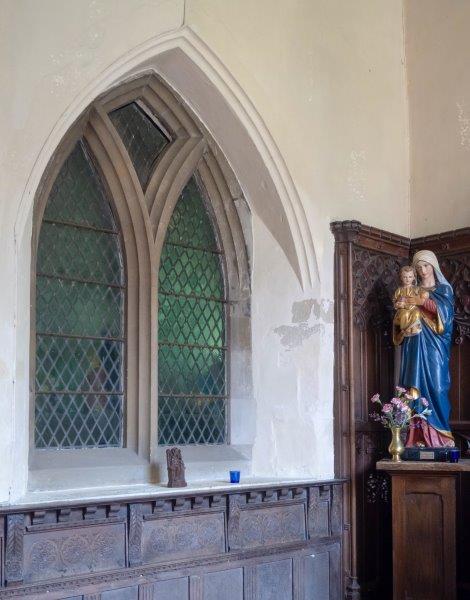

The Paris Chapel was built as an extension to the south aisle and linked to the Chancel by two arches. The original tombs and brasses of the Parys (Paris) family (Lords of the Manor) were here – the 1425 brass on Nicholas Paris still remains. The vestry was also built then, and the old window on the outer wall of the former church became an inside window. There are two low exterior windows in the outer vestry walls, one on the east side and one on the north, which are believed to be leper windows.

The last major structural change came in the later 16th century when the newly important Protestant family, the Millicents of Barham, extended the northern aisle to build their family chapel. An external door provided access and the date 1587 was carved on the lintel. They erected a family monument on the eastern wall in the late 17th century; this is now obscured by the organ.

At that time there were no seats or pews except for the stalls in the Chancel. The walls were coloured and there was a wall painting above the chancel arch depicting Doom and Salvation, with St. Peter shown in combat with the devil for the salvation of souls. There was a gilded and painted rood screen, a platform and a crucifix by the chancel arch.

Beneath the chancel arch is a large black stone monument to Sir Philip Parys who died in 1558 and was a loyal supporter of Queen Mary. He died a Roman Catholic and the inscription “I pray God for mercy to their soules ” was chiselled out by William Dowsing when he visited Linton in 1644 to enforce the 1643 Parliamentary Ordinance against images, inscriptions and idolatry.

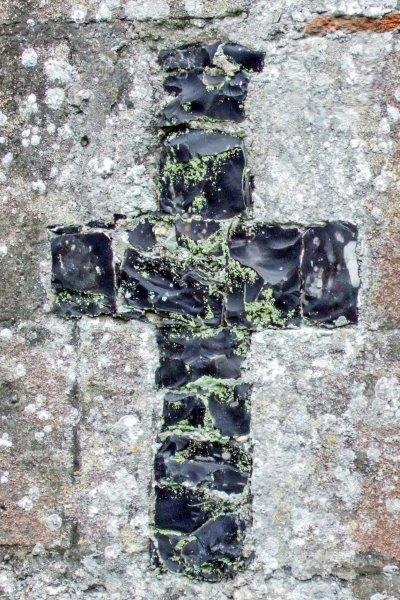

The church tower had a spire, which is shown on the 1600 manorial map of Linton made by the Millicent family. It collapsed and fell through the nave roof in a violent storm in November 1703, however, and was rebuilt as a small bell tower which was removed by 1900. On the outside of the church you can see some of the consecration crosses cut into the clunch which were made when this third church was finished.

The Millicent Memorial

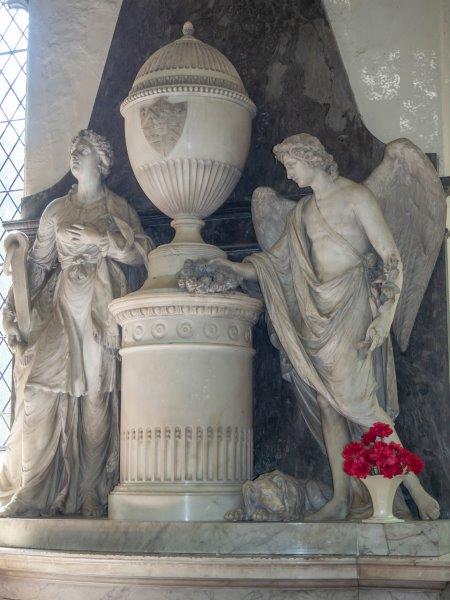

Hidden behind the organ in the Millicent Chapel is an exquisite monument dedicated to Squire John Millicent’s parents and grandmother. Fresh from his triumph over the vindictive Lone family the Squire was determined to consolidate his victory by means of a beautiful monumental structure which would remind future congregations of the importance of the Millicent family in Linton affairs. The precise year of its construction is unknown, but it is most likely to have been completed after the marriage of the Squire to Dorothy Wright in 1705.

The Millicent Memorial was probably so magnificent because the Squire wanted to build a structure which would dwarf the existing Flack and Lone Monuments which were then fixed to the walls of the Chancel, close to the Millicent Chapel. At the top right hand side is the full sized bust of a well dressed woman, John’s grandmother Duglas Wright, the wife of Robert Millicent, who died in 1631.

Beneath Duglas are two full sized figures with their hands meeting on a large skull: her son John and his wife Alice Chester. Hour glasses hang by their sides. John was regarded as a Civil War hero and went on to play a prominent role in Restoration politics. He was a local Justice of the Peace and became the dominant social and political figure in Linton for almost forty years until his death in 1686. The Millicent family were pre-eminent during this period because the Linton Manorial lords, the Paris family, were Roman Catholic recusants and resided in Norfolk.

John and Alice Millicent produced eleven children and the six girls and five boys are shown in shallow relief beneath their parents. John is praised in the Latin inscription as a good husband, a fair and impartial administrator of justice and an excellent leader. There is a reference to their ninth child, William, who showed great promise but died young . All the children save for John Millicent junior (1657 to 1716) died before their father’s death in 1686. Squire John revered his parents and grandmother and this explains why he ordered such a large memorial to be built.

At the bottom of the monument is a coat of arms and a small plaque with an inscription, “under cold marble are buried here the bones of John Millicent gent and his wife Elizabeth (Gulle)”. This John was the founder of the Millicent family fortune and he built the Millicent Chapel shortly before his death in 1577. He had served Thomas Cromwell during the dissolution of the monasteries and acted as a government spy at the time of the Pilgrimage of Grace. Squire John probably left the original small plaque intact and constructed his magnificent memorial above it.

Church restoration after 1870

Our Church had been neglected over the centuries and the building was in a poor state of repair by the 1850s. However, a newly appointed Linton vicar, the Reverend Edward Wilkinson, came in 1859 and was determined to undertake renovations. It required a ten-year battle before the vicar secured majority support in the small group of influential people who controlled the Linton Vestry, but on July 22nd 1870 the Vestry voted by seven votes to six to petition the Chancellor of the Diocese of Ely for a Faculty to remodel the Church, at a cost of around £477, paid for mainly by the Reverend Wilkinson.

The Church interior acquired an entirely new look, very similar to the appearance of our present Church. All the existing pews and seats were removed and replaced with chairs. The floors were made good using four thousand brick tiles purchased from Haverhill, and the Font was re-located closer to the west end of the south Aisle. The old large arch at the east end of the Nave had to be replaced by two arches, and if one views the two arches from the south Aisle it is still possible to see the wide curve of the old single arch in the plaster work. The north aisle gallery (erected in 1790) was pulled d

own, a new pulpit was built into the southern arch of the Chancel and two desks were positioned on either side of the chancel arch.

Upkeep of the Chancel was the responsibility of Pembroke College, and restoration work on this part of the church was completed in 1878 to 1879. The Chancel, the Millicent Chapel and the Vestry were all restored, including repairs to the mullions and stonework, and a new lead roof. A handsome oak reredos was positioned across the whole of the eastern wall, with returns north and south and a new oak altar rail and a prayer desk for choirboys was also installed. Various monuments were relocated to other parts of the church, and the Sclater-Bacon Monument was moved to its present position in the south aisle.

At the same time, the old and inferior organ standing in the Millicent Chapel was taken down and funds were raised for a larger new organ, which was installed in the Millicent Chapel in 1879, completely obscuring the Millicent Memorial.

Church windows

On the southern aisle wall nearest the south porch the various glass shields saved during the restoration of the church (and the only medieval glass in the church) are displayed in a window. The East and West Windows were installed and paid for by subscriptions in 1893. The Isaacson family of Springfield House in Horn Lane and the Chalk family of Chilford Hall were major contributors to the Jesse window at the east end. The West Window was paid for by the Bennett family who resided at Richmonds in the High Street.

The Queen Victoria Memorial Window is located in the north aisle. Originally intended as the Diamond Jubilee Window the window was eventually renamed to commemorate the Queen’s death, since it had taken Linton so long to raise the money!

In May, 1921 the Memorial Window and Oak Tablet with the names of the War dead was unveiled in the Paris Chapel. The Tablet was removed to the north aisle in the 1960s.

Church restoration in the 1960s

The Revd Harry Crichton became Vicar in 1960, and during his time several changes were made to the church interior. Great St. Mary’s Church in Cambridge offered enough good quality oak pews to fill the centre nave at around £20 each. A new heating system was also installed.

In November 1963 a faculty was granted for the restoration of the Paris chapel, which had been used to store brooms and odds and ends. About £1000 was raised and work began in January 1964 on the new Chapel of Resurrection, which was consecrated by Bishop Walsh in April 1964. It was also decided that the wooden War Memorial should be moved to the north wall of the nave, where everyone could see it.

In March 1967 the vicar, an ex-cabinet maker, built a new nave altar in oak and walnut. He took three weeks to produce the altar – 6 feet wide and 2 foot 9 inches tall. The platform for it was built by Ian Gurr and Maurice Biggs, a choir member and apprentice carpenter.

Church refurbishment in the 2000s

A flash flood in October 2001 (a similar flood had occurred 33 years previously) resulted in extensive damage in a number of areas of the village, including the church itself. Despite the best efforts of volunteers to move as many small items as possible to a higher level, carpets, altar frontals and various furnishings, as well as the boiler, were all damaged beyond repair. Services were temporarily re-located to the Village Hall, and humidifiers ran for several weeks in an attempt to dry out the building. A cold and damp winter ensued until a new boiler could be installed in the spring of the following year. Insurance money enabled a new all-seasons altar frontal and kneeler to be purchased for the high altar.

Further refurbishment has seen the fitting of new external doors to the south and north porches and new oak cupboards and shelving at the back of the church. Finally, in order to provide greater flexibility in the use of space, as well as improved comfort, most of the large pews from the centre of the nave have been moved to the side aisles, and replaced by chairs.

Note off-centered arch at east end of nave

Note off-centered arch at east end of nave

And today…

Every generation of Christians, from the earliest times, has reordered their places of worship to facilitate their walk with God. This generation is no different. At St. Mary’s, we are committed to striking a balance between maintaining the heritage of the building whilst also seeking to make appropriate changes that will help us to grow the mission and ministry life of the church.